Japan Is What Late-Stage Capitalist Decline Looks Like

Is America next?

One of the more bizarre and traumatic incidents in Japanese pop culture was when music group AKB48’s Minami Minegishi publicly shaved her head in penance for breaking a band rule.1

The crime? Having a boyfriend in her 20s.

Public humiliation rituals are a typical punishment for the idol industry. So many aspiring pop stars are brutally ridiculed for normal adult woman behaviors. Minegishi’s shaming was just the first incident that was shocking enough to be reported on in the West. The idol industry’s machinery was revealed worldwide for how bestial it truly was: organizing itself on enforced sexual purity, parasocial entitlement, and female infantilization fetishes.

It was portrayed as a cultural quirk — Japan having this ultra-serious, ultra-discipline focused culture where cruelty is an accepted, common sense outcome for rule breaking. But this is essentialist thinking that exoticizes dysfunction simply for it being foreign.

Rather than culture, I believe that this “weirdness” is more attributable to Japan being one of the first nations to enter late-stage capitalist collapse.

The cultural stagnation seen in the US now, was actually predicted decades ago in Japan. Americans now exist under the same structural precarity and economic pressure that produced the “quirkiness” seen in Western perceptions of Japan.

The Economic Engine: Late-Stage Capitalism

The Japanese economy was decimated by World War 2. Major cities were firebombed, the population was traumatized, and food shortages ravaged the country. Prewar Zaibatsu (industrial conglomerates) were dismantled by U.S. occupation authorities to weaken militarism. Japan was on the brink of famine.

Post-war, the U.S. oversaw sweeping economic, political, and institutional reforms to rebuild Japan into a liberal capitalist nation. Land was redistributed to tenant farmers, unions were legalized, monopoly power was broken, and the Dodge Line (1949) stabilized the currency.

Then the Korean war began in 1950, and Japan became the premiere clientelist manufacturing hub for the Americans. This injection of demand kickstarted Japan’s industrial revival.

From that period into the 70s, Japan sustained double-digit GDP growth for nearly two decades and once the 80s hit, Japan became the world’s second-largest economy.

Rapid growth and deregulation led to massive speculation in the stock market, and the Yen appreciated massively. Nikkei stock quintupled and real estate soared — households borrowed aggressively against inflated assets and the country grew comfortable on a sense of economic invincibility.

In 1991, the Bank of Japan tightened monetary policy, cooling speculation which triggered an enormous crash. Asset values plunged by over 80%, and the banks were left with bad loans. This event marked the beginning of the Lost Decade, a period of incredible stagnation that could be better called the Lost Decades — as it plagues the country to this day. Wages peaked in ‘97, the Yen depreciated, and household purchases have flatlined.

America’s “Lost Decade” started with the housing crisis of 2008, where subprime mortgages and the predatory financialization of consumer debt liquified the entire financial system.

Where the Japanese response to the financial crisis was slow and fragmented, the Americans aggressively flooded the economy with liquidity. TARP bailouts, quantitative easing, zero interest rates, and forced bank recapitalization helped Wall Street recover but not the ordinary American. Asset inflation benefited the rich, and everyone else was handed incredible wealth inequality.

In Japan, after 1991 “irregular” employment became common. Part-timers and freeters were stuck in cycles of low-wage, low-security work with no benefits. In the U.S. we saw the growth of the gig economy, zero-hour scheduling, and adult reliance on part-time, no-benefit menial work to get by. Steady middle-class jobs turned into a luxury, only possible to luck into with an expensive college degree.

The downstream social consequences have been significant.

Social Consequence 1: Evil Jobs

Japan has a term for “evil jobs” — ブラック企業 (Black Kigyo or Black Labor). These jobs enforce extreme overtime, unpaid labor disguised as “service overtime”, surveillance, and quotas. Workers internalize this obedience and labor abuse because the alternative is unemployment and social stigma.

Black kigyo companies comprise a significant portion of entry-level work, drastically altering working norms for young adults.

American analogues are now visible too. This November, the private sector lost 32,000 jobs.2 The pandemic-era white collar work bubble popped, and popped hard. Hiring is flat for the Class of 20263 as layoffs rise and AI takes over menial white collar labor. The American worker is being pushed into gig-worker exploitation, and human dignity violating work conditions. Even industries that were typically seen as relatively stable — healthcare and education — are experiencing major worker burnout.

Overwork is normalized. Karoshi (”death by overwork”) became a recognized cause of death in the 1980s. This includes heart attacks, strokes, and suicides linked to workplace abuses and poor life quality. If you visit Japan you may see signs of this normalized absurdity: salarymen collapsed in random public locations, Konbini selling shower-in-a-can, and people getting most of their calories at vending machines and subway station kissaten.

The average American, unfamiliar with Japanese social norms or cultural history, likely thinks this is some reflection of premodern Japanese values or ritual suicide traditions. It’s not.

Karoshi directly parallels emerging American trends in burnout-related deaths and mental-health collapse. Amazon, for example, had to make a public apology for denying their drivers the right to go to the bathroom.45

Social Consequence 2: Atomization

Japan has an incredibly high rate of single-person households. 34% of all households are just one person – generational ties are collapsing at an alarming rate.6

Third spaces do exist, but work dominates social life; friendships for many are hard to maintain, and socialization is often work-place bound. An estimated 1.5 million Japanese people have chosen to withdraw entirely from society, in a phenomenon known as hikkikomori.7 They live at home as recluses, rarely leaving.8

The U.S. now has a similar issue. There are countless think pieces now on the American loneliness epidemic. Estimates of friendless Americans range from 8% to 12%.910 The Survey Center on American Life reports that the amount of time the average American spends with their friends has collapsed by half compared to survey data from a decade ago.11

Further, Japan’s birth rate has remained below replacement for decades. Marriage is financially prohibitive. Gendered work expectations (and dual income pressure) force women to opt out of child rearing entirely, and men opt out due to economic precarity.

Marriage and children become status symbols that most young adults cannot achieve.

The U.S. birth rate has hit an all time low.12 People marry later, and even still with combined finances feel unable to financially support a child. The typical progression of marriage, homeownership, then children is constipated at step one.

Housing demands two incomes just to qualify, student debt makes fusing finances risky, and healthcare costs mount the more dependents you have. Children are, economically, a net loss. You have a baby? Now you have to foot the bill for childcare, education, healthcare, lost labor time, and housing. Parents receive no state support, no childcare, and flimsy labor protections. The rational outcome is that people choose not to reproduce or expand a family.

Social Consequence 3: Convenience Slop

I mentioned Konbini food earlier, and it gets romanticized in travel media as a “wow Japan is so cool” cultural object.

The convenience culture is not leisure culture. It’s a substitute for home life in a society where people lack the time to cook, rest or socialize. The U.S. has equivalents – Sweetgreen, Chipotle, Uber Eats, Amazon Fresh – all reflect the same shift toward outsourced domestic functions.

Even these fast casual worker-trough food places are facing market decline. The Gen Z consumer can’t even afford a bowl from Chipotle anymore.13 Going out is generally pointless unless you have an entirely Sysco curated palate; the food distributor dominates the restaurant industry. Local businesses flounder as people lose the discretionary income to go out; the ones that stay open just microwave whatever fell off the back of the Sysco truck.1415

People opt for these choices because they lack the time and resources to cook regularly. The market supplies to them instead delivery platforms and heat-and-eat quick foods.

In 2022, Americans on average only had 8.2 of their weekly meals prepared at home.16 It doesn’t sound bad at face value, but imagine saying this to your grandparents. Imagine explaining that this was because people lacked the time. Personally, mine would be flabbergasted. I’m curious too – how many of these meals are actually home cooked? How many of them are Sysco-backed frozen foods?

Sure, survival becomes frictionless – logistical inconvenience is cut out. But is it enabling leisure or is it a prosthetic for a society that has lost personal time?

Social Consequence 4: Weird, Hypersexual Media in a Sexless Society

Sexual activity has declined wildly. I suspect it’s not at all controversial for me to say that sexual intimacy is a normal human need, and an element of a happy life.

Japan is a sexless nation.

“Japan has the lowest sexual frequency in the world, and it is the only country where the percentage of people who are not happy with their sex life is higher than that of those who are.”17

In the quoted survey, sexlessness is defined by having sex less than once a month. 19% of partnered individuals in their 30s surveyed described being sexless by this definition. Nearly half of all Japanese millennials (18-34) were virgins in 2016.18

Call me a harlot, but I see sex as being a normative prosocial behavior. If individuals are interested in sex, but unable to obtain it, it typically indicates a major social deficit. Normal relational and life milestones are being missed. Nearly 1 in 3 American men reported no sexual activity in 2020.19 Gen Z is afraid to have sex.20 24% of Americans 18-29 report having no sex in a year.21

Dating requires a few factors to happen: disposable income, a stable schedule, and housing privacy. Late stage conditions produce irregular work hours, high costs of living relative to wages, and people living with their parents or roommates into mid-life. Relationships, or even casual sex, become logistical drains.

Parasociality becomes a pressure valve for unmet intimacy needs.

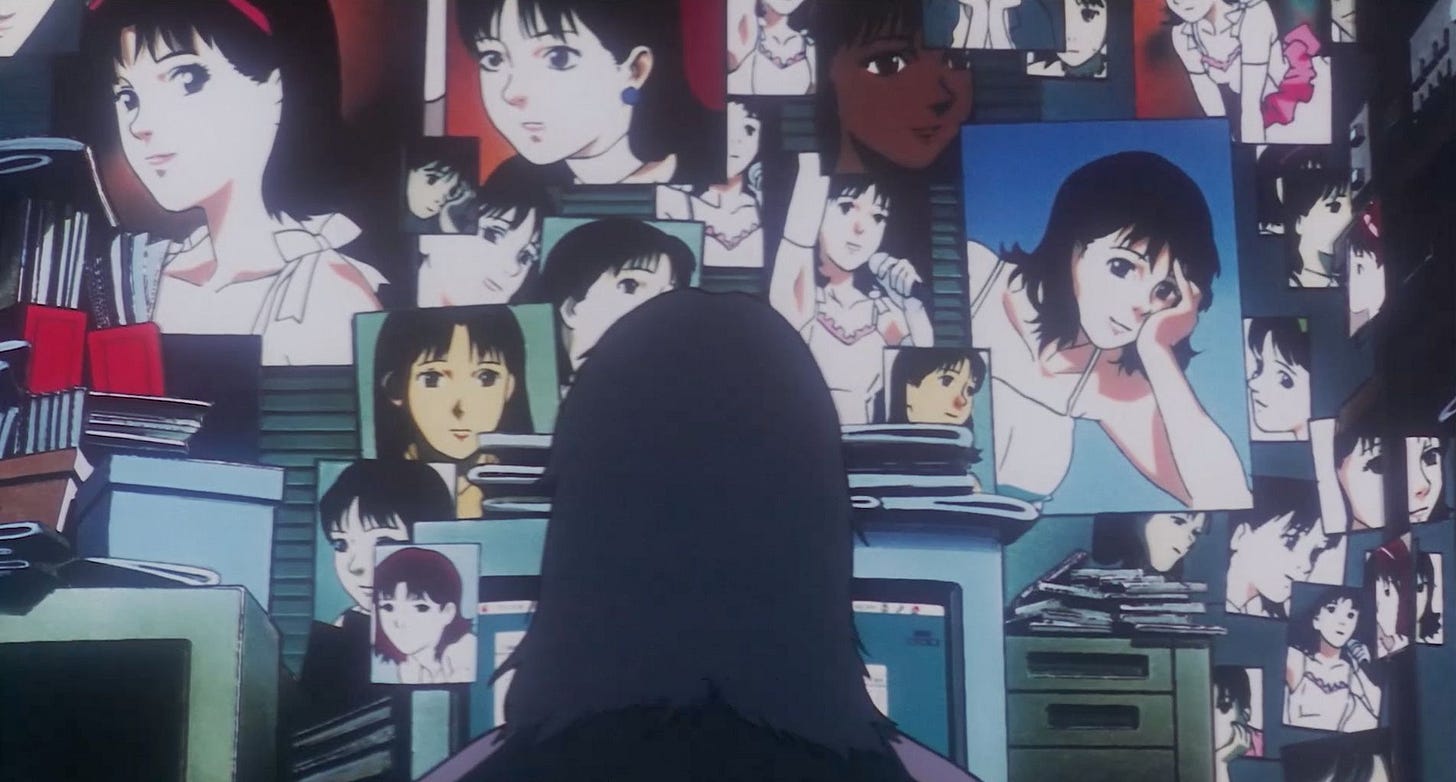

Idols function as emotional surrogates in a society where adult intimacy is not just difficult to achieve, but structurally inaccessible. These cute, frill adorned women are not like the American popstars meant to appeal to a young female fanbase. Rather, their groupies are older men who entrench themselves in a parasocial obsession with the young, often minor performers.22

The “no-dating” rule that these groups and their labels enforce are meant to maintain the illusion of availability and sexual purity to lonely men.

Parasociality emerges because real relationships require stability and time investment — neither accessible to the average Japanese worker.

Traditionally, celebrities existed behind a barrier. Fan engagement was limited to managed press releases, magazine interviews, and staged performances. There was a finite flow of personal information to the public. Idol culture breaks that boundary, and frankly American influencer culture does too.

Fans now access ongoing, unfiltered streams of personal content where the celebrity is necessarily a fictitious character in everyday life. Idol systems monetize emotional deprivation — handshake events, loyalty expenditures, and micro-intimacy displays as merchandise. Influencers replicate this through daily vlogging, livestream Q&As, DM responses, Cameo-style personalized videos, and Patreon subscriber tiers. Hell, in the US you can even sometimes purchase the sex of your favorite influencers via their Onlyfans accounts. Intimacy is entirely transactional and the entire human — from body, mind, and ordinary life — become consumer products.

Just like how idol fans enforce when idols can date, marry, break up, or have intimate relations, influencers experience just the same with subscriber drop-off or harassment after announcing a relationship. The idol is not admired for their art; their personhood is the product and that same economy has been laundered to the US in a different form.

Predictive Value?

Japan’s conditions create a map of where the U.S. is heading unless significant structural changes occur. We’re seeing intensified overwork culture in a stagnant job market, parasocial intimacy becoming a substitute for human connection, and convenience replacing domestic life. There is slow collapse of dating, shrinking fertility rates, and a pattern of young adults dropping out of social life under economic pressures.

Japan isn’t a quirky outlier – it’s simply a society that started its capitalist decay earlier. And that decay looks surreal.

In a functional society, basic human milestones are incentivized. You want to form relationships, get married, buy a home, and plan for the future. In late-stage capitalism these same milestones become financially punishing and logistically impossible. The incentive structure flips into absurdity – what should be rewarded is punished and what should be discouraged becomes adaptive. Unhealthy social behavior looks maladaptive or irrational until you look at the material reality – owning nothing, living in pod, and eating bugs is rational in an irrational economy (lol).

This article is a bit intense, but it does capture something real. And we do hope our generation can do better with sexism and gender norms. Yet somehow we still manage to find a lowkey kind of happiness in a place like this (maybe we’re just too adaptable?)

There has even been a long-running debate about whether Japan should be understood as premodern or postmodern. We sometimes say “Japan is peacefully hellish, or a hellishly peaceful place.” We tend to have a fairly critical view of our own society, but we honestly have no idea what to call it.

After the pandemic most young people just started drinking chu-hai from the convenience store and hanging out on the street, having fun in their own way. Maybe we really do look kind of unhinged from the outside. It’s just a little case of our everyday life in this quiet chaos 😇

This is such a thoughtful, well-structured piece. The reality it describes is horrifying though. It feels… very bleak. Is there much movement and appetite for change in the wider society, do you think? Or do people just think it’s hopeless? Rebellion is hard within the confines of the rigid societal structures.

The bit about the pop star shaving her head feels medieval. And the most shocking thing for me is that she has acquiesced! Is she still active in the industry?

I will send this to my dad who lived in Japan in the 60s as a kid.